Amazing Indoors

The New California Academy of Sciences

This article first appeared in The Boston Sunday Globe, 10/12/08

Most museums, Italian architect Renzo Piano says, are "kingdoms of darkness." Sunlight fails to penetrate them, with exhibits protruding from windowless walls.

The California Academy of Sciences belonged in this category, until a 1989 earthquake shook its foundation, literally and figuratively. Given the opportunity to rebuild, officials pondered how to reinvent the institution, the oldest science museum in the West, and transport its millions of specimens - 700,000 pinned butterflies, a 70-year-old Australian lungfish, and an albino alligator among them - into the future.

Competing architects presented one elaborate design after another. When Piano arrived from Genoa, however, he brought only his daughter, the story goes, along with a sketchpad and a green felt-tip pen. "How can I know what to suggest when we have had no conversation?" asked Piano, whose prized work includes the Pompidou Center, the Whitney Museum expansion, and The New York Times building. No two of his structures are alike, his devotees say, because of his collaborative nature and attention to local conditions.

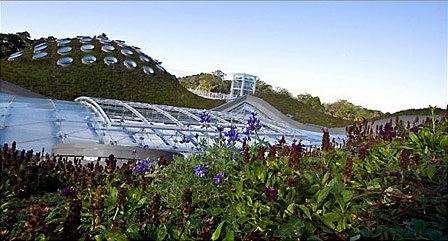

He got the job, and eight years later the riveting 410,000-square-foot design has recently opened to the public. An airy, glass-and-steel facade capped by a 2 1/2-acre living roof of native plants that is already attracting birds and butterflies, the new Academy stands just across the Music Concourse from the opaque-walled, equally riveting de Young art museum. (Each museum has a new two-level underground garage for visitor parking, preserving the open space around them.)

Replacing the Academy's former 12 buildings, the new facility houses a natural history museum, aquarium, and planetarium under one roof, along with laboratory facilities. While most research is sequestered on lower floors, one of the building's imaginative trappings is a glass-walled lab on the first floor through which visitors can watch researchers work. An exhibit "Science in Action" also focuses on research, with six flat-screen monitors providing up-to-date science news.

Piano wanted, as he put it, to "metaphorically lift up a piece of the park and put a building underneath." And, from within, a visitor indeed feels at one with the landscape. Standing midpoint in the building, in its dramatic glass piazza, you can look front or rear out at the park. Transparency, and not feeling trapped indoors, is what Piano was after.

Left of center, the 290-seat Morrison Planetarium rises up, its enormous dome forming one of several hills on the living roof. Right of center, a four-story tropical forest similarly ascends through the building, a winding walkway taking visitors past live birds, poison dart frogs, and geckos. Its dome, filled with round skylights that allow in ample daylight, represents another hill on the roof, as seen from the roof's observatory deck.

The manner in which the Philippine Coral Reef exhibit and its 3,000 fish are tucked under one side of the planetarium, or the African Hall and its dioramas, a retained section of the old Academy, are brought alive with tottering penguins, are fascinating parts of a surprising whole.

But perhaps most impressive is the way both the architecture and the exhibits embrace sustainability. The Academy's design goes so far in this direction that it has received an LEED certification at the Platinum level, the top mark handed out by the US Green Building Council. It is the largest museum in the world to have earned the distinction. (According to the council, there are currently 90 Platinum projects completed in the United States, with California's 950,000-square-foot Environmental Protection Agency building so far the largest.)

The Academy building itself serves as an exhibit about sustainable practices. Ninety percent of the old Academy was recycled. Altogether, 11 million pounds of recycled steel went into the new building as well as 137 million pounds of locally-sourced concrete, which was mixed with fly ash and slag, two normally discarded materials left over from making steel, so that less new concrete was needed.

Museums apparently consume twice the energy used by office buildings because of their extended hours and controlled climates, a trend this museum fights. Numerous features help with conservation. There are louvers that let in sea breezes on warm days, plentiful skylights but also sun shades, a canopy of 60,000 photovoltaic cells bordering the living roof, radiant floor heating, and insulation composed of shredded discarded blue jeans. Even the piazza's high glass ceiling cranks open to the sky to let in fresh air.

Asked what pleases him most about the design, Gregory Farrington, executive director, responded, "I love the fact that you can open the windows; what an extraordinary concept!"

For the Steinhart Aquarium's exhibits, seawater is piped in from the ocean. It used to be that used exhibit water was thrown out, but these days "because of the EPA, we return water to the ocean cleaner than it comes out," said Farrington.

While many of the green aspects of the building are more hidden, the subject of sustainability, coupled with those of evolution and biodiversity, is front-and-center in all 15 exhibits. "Water Planet," for instance, looks at the relationship between water and life; "Altered State" examines the impact of global warming; and the tropical forest display underscores just how many animal species are supported by these vulnerable paradises.

While there is much to admire here, there are flaws. The planetarium's opening show, "Fragile Earth," is disappointing due to an unremarkable video and lackluster script. On the first floor, back-to-back exhibits in some spaces cause confusion as to where one stops and the other begins.

Overall, however, extensive data delivered by flat-screen monitors, touch screens, and other digital wizardry make exhibits fresh and absorbing. The focus on being eco-wise extends into the museum's two restaurants, where local sustainable foods are offered; into the three stores, stocked with wind-power kits and nature gizmos; and even into the bathrooms, which feature low-flow toilets, futuristic low-energy hand dryers, and quotes by environmentalists.

Putting together such an extravaganza of a building wasn't easy, admit those involved. It took years, for instance, to figure out how to let enough light into the rain forest for plants to grow without heating adjacent halls where there is no air conditioning.

My concern about the museum's sizable biospheres - the 25-foot-deep coral reef is the deepest interior example in the world - is the hardship of properly maintaining them.

Nevertheless, most will agree that the hefty admission fee ($15-$25) is worth it, given the dimensions of this bold experiment and its creators' great regard for planet Earth, as conveyed by attention to large and small detail. Note that the benches in the hallways and the casework in the stores are made from the wood of fallen trees found in the park. And note, as you leave, the Pledge Station. Just as Cal Academy has done, you, too, can vow to live as greenly as humanly possible.

|